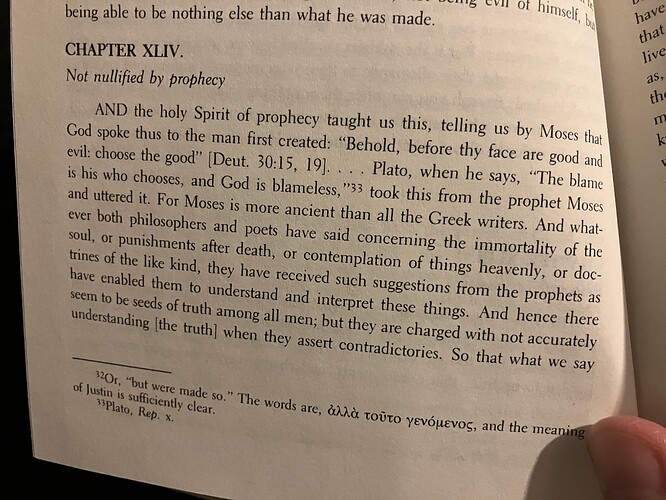

Justin Martyr (100-167) contended that Christians were innocent of certain charges against them. He also contended for the truth of Christianity. He makes strong appeals to prophecy to show the truth of Christianity. Much of the writing of the early apologists was to counteract the accusations and persecutions they were facing from pagan authorities. But are his apologetics not disputed?

Athenagoras (c. 133–190) was heavily influenced by Platonic and Stoic philosophy. Some scholars argue that he presents Christianity more as a refined philosophical system than as a distinct religious faith, making his approach different from other apologists like Justin Martyr. Unlike Justin and other apologists, Athenagoras rarely quotes Scripture explicitly. This has led some to question whether his arguments are truly rooted in Christian theology or if they are merely an attempt to make Christianity palatable to a Greco-Roman audience.

Additionally, because Athenagoras does not mention his conversion or provide personal details about his faith journey, some scholars have even speculated whether he was a Christian or simply a philosopher defending Christians on philosophical grounds. His description of God, the Logos, and the Holy Spirit is considered relatively undeveloped compared to later Trinitarian formulations. Some theologians have debated whether his theology aligns fully with Nicene Christianity.

Irenaeus of Lyon (c. 130–202) has been both influential and controversial, particularly regarding his portrayal of so-called heresies in his major work, Against Heresies (Adversus Haereses). He provides one of the earliest and most detailed critiques of Gnostic sects, but many scholars believe he misrepresented their beliefs. Since we now have original Gnostic texts (e.g., the Nag Hammadi library), it is clear that some of his descriptions were exaggerated or oversimplified. His account tends to frame all Gnosticism as a singular, unified movement, whereas in reality, it was highly diverse.

Also, Irenaeus wrote from a polemical stance, portraying “heretics” as corrupt and dangerous. His approach has been criticized as unfairly demonizing alternative Christian traditions, especially those that were later suppressed. His theological positions, particularly his view of apostolic succession and the authority of the Church, have been debated. Some argue that his emphasis on hierarchical authority contributed to later rigid structures in Christianity and suggest that he created a false dichotomy between “orthodox” Christianity and “heretical” movements when early Christian thought was far more fluid.

Tertullian (c. 155–235) is often accused of exaggeration, particularly in his Adversus Marcionem (Against Marcion), where he critiques Marcion of Sinope, an early Christian thinker who promoted a strict dualism between the “vengeful” God of the Old Testament and the “merciful” God revealed by Christ. He presents Marcion’s theology in an extreme and simplistic way, portraying him as entirely anti-Jewish and irrational. Modern scholars, especially with access to reconstructed fragments of Marcion’s Antitheses, argue that Tertullian exaggerated or even distorted Marcion’s views to make them seem more absurd.

Tertullian doesn’t just critique Marcion’s theology but also attacks his character, accusing him of being motivated by pride and wealth. He even claims that Marcion’s followers were immoral, an accusation often made against so-called heretics without solid evidence. And Tertullian’s claim that Marcion single-handedly corrupted Christian doctrine probably overstates his impact, because some scholars argue that Marcion was responding to theological debates that already existed rather than inventing an entirely new system.

Origen (c. 185–253) relied heavily on Antiquities of the Jews by Flavius Josephus, particularly when discussing historical events related to Judaism and early Christianity. However, Josephus’ reliability has been a subject of long-standing debate, especially regarding his motivations and biases. One of the most famous passages in his Antiquities (Book 18) appears to reference Jesus, but scholars widely debate its authenticity. Origen, in his Commentary on Matthew (Book 10), mentions that Josephus did not believe Jesus was the Christ, implying that he had access to a different version of the Testimonium Flavianum. So, it appears that later Christian scribes may have altered this passage, making Josephus seem more favourable to Jesus than he originally was and bringing doubt on his record.

While Origen found Josephus useful for historical context, he also indicated at the historian’s limitations. Scholars continue to debate how much of Josephus’ work, particularly passages concerning Jesus and early Christianity, can be taken at face value. Josephus was, after all, a Jewish historian writing under Roman patronage, particularly for Emperor Vespasian and his successors.

Athanasius of Alexandria (c. 296–373) is seen as a towering figure in early Christianity, known for his staunch defence of Nicene orthodoxy against Arianism. However, his career and writings are not without controversy, both in his personal conduct and in the way he engaged in theological disputes. He was accused of violence and corruption, including the alleged murder of a rival bishop (Arsenius, who was later found alive). His enemies used these charges to have him exiled multiple times. While he presented himself as a victim of heretical conspiracies, his own tactics were often aggressive.

On the Incarnation, and his anti-Arian polemics were foundational for Nicene theology. However, his portrayal of Arius and Arianism is often seen as distorted. He presents Arius as teaching a crude subordinationism that many scholars argue is a caricature. He describes Arians as “madmen,” “heretics,” and “enemies of Christ”, making little effort to understand their views beyond refuting them. This kind of rhetoric shaped later Christian attitudes toward heresy.

Athanasius was a strong supporter of monasticism, particularly the Desert Fathers like Anthony of Egypt. However, his promotion of monastic ideals also led to tensions. Some sources suggest that monks loyal to Athanasius acted as enforcers, intimidating his opponents in Alexandria. While revered as a Church Father, his legacy is not without disputes regarding his tactics and theological polemics.

Augustine of Hippo (354–430) is one of the most influential figures in Christian theology, but he remains highly controversial for several reasons. His intense self-criticism and rigid theological stance have led many to view him as a man compensating for his earlier life. But some scholars argue that his self-condemnation was exaggerated and possibly served a rhetorical purpose. Remember, even before converting to Christianity, Augustine was a skilled orator and teacher of rhetoric, seeking fame and fortune.

Early on, he was a follower of Manichaeism, a dualistic religion that saw the world as a battleground between good (spirit) and evil (matter), but later, he became one of its fiercest critics. Some wonder if his deep attachment to strict dogma carried over into his Christian theology, which was deeply shaped by his personal struggles, particularly his belief in original sin and predestination, which is excessively pessimistic about human nature. His lamenting his past lusts, including his long-term relationship with a concubine, with whom he had a son, may be the source of his intense guilt about sex, which influenced his later views on original sin and celibacy.

Early apologists seem to be rather taken to bullying it seems.