The curious case of an unremarkable man who could, literally, read the world

For those familiar with Buenos Aires, few places offer as picturesque an atmosphere as the small but charming neighborhood of Palermo. Famous for serving as a contrast to the capital’s typical bohemian bustle, it’s known as the neighborhood of Argentine poets, and not just because it inspired many Borgesian musings. Its tree-lined avenues, parks, and grand old mansions all contribute to Palermo’s slightly idyllic atmosphere, serving as both a complement and an escape from the typical frenzy of the porteños. Walking through Palermo is like traveling back in time and arriving at another era, a time of pioneers and explorers in Argentine history, a time of strong Italian (Sicilian) influence, crystallized in the famous Plaza de Italia, with its famous monument to Garibaldi.

Notable among the city’s buildings are its decaying mansions, many of which are now being adapted by the spirit of renovation as hotels, restaurants, apartment buildings, and more. These enormous houses, built under the strong influence of Italian architecture, as the neighborhood’s name suggests, served as homes for many of the country’s wealthiest families. However, as time passed and Argentina’s social makeup underwent radical transformations, they fell out of fashion. Today, they serve more as a reminder of a glorious past than an indication of wealth or prowess.

It was in front of one of these old-fashioned mansions, located on the neighborhood’s most popular avenue, Avenida Sarmiento, that Pablo Herrera Corrientes’ modest vehicle, a yellow Chevrolet Classic, stopped on a rainy summer day in 2015. He couldn’t remember the last time he’d been to Palermo. For many years, he had worked and lived far from the capital, in the city of Tucumán, in the northwest of the country. The reason he had come so far to visit that enormous house, which at first glance seemed completely deserted, was that the owner, his only brother, Juan Herrera Corrientes, had died there two months earlier from a sudden attack reported to the police by his only employee, a certain Venancio, whom Pablo never met, as the guy had moved from Palermo shortly after his boss’s death. All Pablo could gather from the police and the doctor who examined the deceased was that he had an unknown form of dementia, in an advanced stage, and had lived alone with Venancio in that house for at least thirty years. He took no specific medication, except sleeping pills. And despite his illness, he managed to gain enough lucidity in his final months to make a will, leaving the money he had saved to Venancio and the rest of his estate to Pablo, his only remaining living relative. Juan was 65, Pablo was 55. The two hadn’t seen each other for at least 20 years.

Upon learning of his brother’s death, Pablo was initially shocked. Amidst his daily activities as the owner of one of Tucumán’s largest supermarket chains and caring for a family of eight children, he rarely thought about Juan or his parents. The Corrientes family was a wealthy merchant family from Recoleta, the most prestigious neighborhood in Buenos Aires, the kind that lived without major problems even amid the country’s greatest crises in the turbulent 20th century. His mother, Henriqueta, and his father, Enrico Herrera, both of Italian-Spanish descent, had married shortly before World War II and had a daughter before his two brothers, who died at just two years old, of undisclosed causes. His mother had decided that she would never have any more children, but Enrico insisted on being a father, and Juan came into the world in 1950, followed by Pablo ten years later.

What Pablo remembered from his childhood and youth growing up alongside Juan was that his brother was a completely normal guy, though usually quiet and reserved. The two rarely played together when Pablo was a child; he remembered his brother preferring to study, read, or do puzzles. With the age difference, the two ended up having different friends, and Pablo grew up, became a teenager and an adult, believing that his brother disliked him for some reason he didn’t quite understand. It wasn’t a real dislike; it was more like he couldn’t live up to his brother’s expectations. But since Juan was so quiet, he never knew what his brother expected of him. However, even with this distance, he loved his brother and was happy with his success. Juan didn’t seem to have the same difficulties as Pablo in studying or finding a job. His difficulties were the opposite of Pablo’s. While Pablo was communicative and outgoing, Juan was quiet and kept to himself, only speaking when necessary. But he always managed to pass with high grades and excelled in any task he set his mind to. Pablo felt an inevitable pang of envy when his father scolded him for his low grades and encouraged him to imitate his brother. But he didn’t know how he could imitate his brother more, because he did everything he did, but couldn’t achieve even half as much success.

When Pablo turned 15, and Juan was 25, Enrico suffered a sudden cardiac arrest that killed him at the age of 47. By this time, Juan had already graduated as an architect and lived alone in an apartment in San Telmo. Pablo stayed with his mother, but her mother, distraught over her sudden widowhood, fell ill a few months later and died, also of cardiac arrest, eight months after her husband’s death. Pablo went to live with a maternal uncle in Tucumán. From then on, he saw Juan only rarely, at the few family gatherings he attended. Every time he (Juan) saw his brother, he didn’t show much sentimentality, but he would ask how he was and if he needed anything. Juan had established himself as an architect and even married, despite his shyness, at age 30. The marriage didn’t last and didn’t produce children, but Pablo attributed this to his brother’s introverted nature. In everything, Juan gave him the impression of being a completely normal guy, with nothing special except, perhaps, his talent for performing well any task he had to undertake. He attributed this to his father’s solid, though never overly strict, upbringing.

As he recalled these things, Pablo took the keys from his pocket and opened the enormous steel gate to the property, a beautiful old colonial-style mansion with three spacious floors, a minimalist yet understated design, a vast backyard with a small wooded area and a swimming pool, a look of neglect both from the leaves scattered throughout the yard and pool and from the dust on the enormous greenish-tinted glass windows. Opening the enormous, antique wooden door, which appeared to have been recently painted, Pablo entered the enormous house, noticing immediately that everything was exactly as it had been since his brother’s death. The furniture was covered with white cloths to keep dust away. The first thing that caught his eye was the property’s impeccable decor: the walls appeared to be covered in a high-quality wallpaper, the furniture was also made of the finest wood, and the floor was covered in a wooden carpet reminiscent of mahogany in its durability. He had never visited his brother’s house, not even when Juan personally invited him before his wedding. Entering that unfamiliar yet strangely familiar space reminded him of the brother he had grown so distant from. As he walked through the building and observed how everything was carefully in its place, he realized what was familiar. Juan was extremely protective of his belongings and detested disorganization. He hated even a sock out of place. He hated dirt as much as clutter. He was always clean and tidy. Arriving in front of a beautiful mirror with an antique wooden frame, Pablo remembered a moment in his childhood when his father had forced him to look in the mirror and see how dirty and unpresentable he was, admonishing him to follow the example of his well-groomed brother.

Pablo spent some time examining the house, realizing that everything was in excellent condition and could fetch a good price to a buyer interested in restoring antique furniture. He had no intention other than to get rid of the property as soon as possible, increasing his large family’s wealth. He went to the kitchen, which was as spacious as all the other rooms, to see if he could find water or something else to drink. In the kitchen, he sat in a comfortable mahogany chair, opened a bottle of mineral water from the pantry—which for some reason hadn’t been completely emptied—and began to admire the beautiful architecture. Every wall finish, every detail of the furniture—everything betrayed a meticulousness he found difficult to associate with a busy architect with only one employee. But the fact is, he “felt” the presence of Juan’s meticulous spirit there. His brother’s good taste was undeniable. Then, a detail caught his attention: a black glass door right next to the laundry area. What was it for? Curiosity drove him to check it out. Then he realized the door led to a small hallway that represented the entrance to a sort of basement. There was at least one underground room in the property. He headed there and noticed a trapdoor leading to a staircase. This staircase, also made of hardwood, already made it clear that it had been built by Juan, given its quality. He still had plenty of free time to prepare things before leaving Buenos Aires, so he couldn’t resist going down and seeing what his brother was hiding in the basement of his mansion.

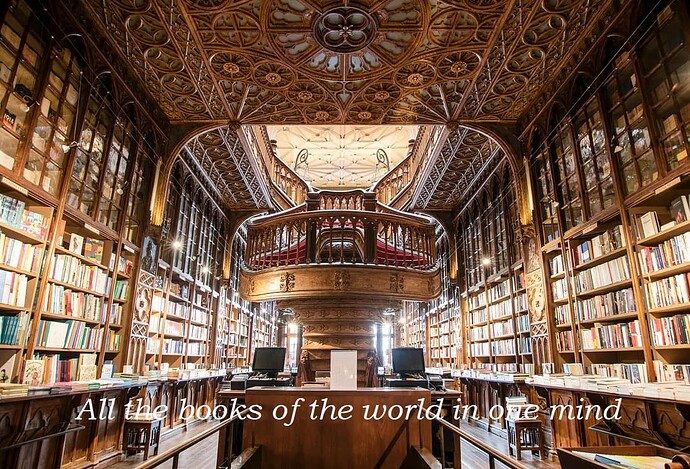

In truth, he couldn’t quite believe what he saw. There wasn’t a mere room or basement beneath the house, but a complete structure. There was another house beneath it, but apparently even larger than the main one. His jaw dropped when he realized that descending the grand staircase led to what was actually an entrance hall. This hall led to a vast room, at least 5 meters high, surrounded by enormous wooden shelves running its entire length, each filled with books, carefully lined one by one, with admirable care. But as astonished as he was to admire that beautiful library, something he had never seen before, he was even more surprised to realize that this was only the first underground floor. There were four more. The house was actually larger underground than on the ground floor. And the ground floor paled in comparison to the beauty of its other half, invisible to the eye of passers-by.

Pablo took a deep breath, sat in a comfortable leather armchair next to what appeared to be one of the many study tables in the place, and tried to imagine what he could do with this place. Even more so, he tried to think of what had motivated his brother to build an underground palace in the heart of Buenos Aires, completely at odds with the atmosphere the city had assumed in contemporary times, that of a bohemian metropolis. He knew Juan was a learned and cultured man. But he hadn’t imagined his brother was the sole owner of what seemed to him, roughly, at least 100,000 books. There seemed to be room for everything on those shelves. Enrico Herrera had encouraged his sons to study and was himself a highly educated man, though certainly not erudite. But Juan seemed to take it to its extreme. For it wasn’t just about books. There were long stretches of wall space devoted to paintings, many paintings. Some by artists Pablo didn’t recognize. Others were impossible to recognize. There were also many sculptures scattered throughout the enormous halls. Works carved in wood, plaster, and even copper were all Pablo had difficulty recognizing. He wasn’t particularly versed in sculpture. Then he had a new surprise when he looked closely at a beautiful plaster bust in the center of the second hall, which resembled Júlio Cortázar, the great Argentine writer. On the lower corner of the neck, the initials JAH were clearly inscribed. His brother was the author of that impeccable piece.

In several of the beautiful paintings on the walls, he also discovered the initials JAH. Juan was a sculptor and painter, and a highly talented one. Was he also a writer? A musician? It didn’t take him long to discover that he was. He discovered a whole row of books he’d written, as well as a series of handwritten scores. One collection in particular caught his eye: The Entirety of History Up to Here. It dated 1998. But curiously, it bore no publisher or publication information. It was an edition his brother had made for himself. Why? Why keep so much knowledge to himself? Pablo was so astonished by everything he’d seen that he decided to call his wife and inform her that he wouldn’t be returning to Tucumán until the next day. He was utterly fascinated by the enigma that this unknown brother represented.

Pausing to think and think clearly, Pablo began to ask: what was the point of all this? Why didn’t anyone tell me that this house had an entire building underground? Did no one know except Venancio? And what am I going to do with this multitude of books? It’s clear that all these things were my brother’s life; I can’t just sell them off like they were nothing. Then he remembered the will. Juan had expressly stipulated that Pablo would inherit the house and “everything in it.” There was no doubt that he was now the owner of all that. Then he asked himself: if his brother was a writer, he must have left somewhere more precise instructions regarding his wishes regarding those works. He certainly wouldn’t want him to simply sell off that multitude of books like waste paper.

After wandering the corridors of the enormous rooms a few times, he noticed that in the center of the third room, which seemed to represent the center of the building itself, there was a beautiful dark mahogany desk, as impeccable in appearance as all the other furniture in the house. On this desk, a huge notebook made of a special type of paper Pablo had never seen before caught his eye. Its open position indicated not only that Juan had written in it recently, but that it had been left open for the sole purpose of being seen by anyone entering the room. It took Pablo a while to realize that the notebook was open for him to see. It was a diary. Written clearly, with spelling as impeccable as it was legible, on the cover read: 2010-2019. In other words, it was a diary intended to cover his life during those years. But halfway through the diary, the counting of the years was interrupted by a linear narration, with no time reference. Intuitively, Pablo realized that this was a summary of Juan’s life, written for him, Pablo, to read. He sat down in the beautiful, comfortable chair in front of the desk and began to read:

“My name is Juan Herrera Corrientes. I am 60 years old. I am writing this, beginning precisely on October 6, 2010, at 9:07 p.m., to leave a written account of my time in this world and, more specifically, as a final effort of concentration and a Herculean attempt not to succumb to forces that, with each passing day, threaten to crush me more relentlessly. I feel my brain already beginning to succumb under the weight of so much knowledge. The fact is that my burden in this world is greater than any other man has ever had to bear. I, Juan Alonso Hernandez, architect, successful and socially respected man, solitary by conviction and temperament, suffer from the greatest of all problems. I know everything.”

When he read this part, Pablo felt a slight jolt, but this could be attributed to the strange situation of penetrating into the intimate world of this brother he had barely known. The fact is that Juan’s shyness ran in his family. Pablo didn’t like sharing his secrets or sharing intimate details with others either. He married a woman, Felicia, who perfectly matched his personality. What set him apart from Juan was that he shared the social life of the upper classes, enjoyed parties, events, and entertaining. Juan, on the other hand, only attended events casually and on occasions when his presence was unavoidable. He was extremely unsociable, and for this very reason, his family created an aura of mystery around him. It was now his curiosity to penetrate the private universe of this brother, this stranger, that drove him. Above all, what made him curious was the statement “I know everything.” Know everything what, exactly?

"Yes, I know everything, all the things, everything there is to know. But if today the weight of that realization is becoming more than I can bear, it wasn’t always this way. The first thing I remember in life is being lovingly picked up by my father moments after I came into the world. I couldn’t say exactly what I felt at that moment, whether comfort or relief at having left that claustrophobic prison straight into the welcoming arms of a living, breathing creature. The fact is that even before I was born, I felt and perceived myself alive. But I couldn’t express anything because I lacked contact with the world outside the womb, where words are used, repeated, and memorized, and words are necessary to describe sensations. Before I was born, I had the sensations, but I didn’t have the words to describe them. It was an uncomfortable situation, and I was relieved when it ended. After I was born, already in my father’s arms, it was as if things began to clear up, timidly, slowly, but little by little, the words began to be found that corresponded to my feelings. It didn’t take me long to realize, for example, that my mother was very unloving. My father was the only parent who truly showed me affection, and from that point on, I developed an inordinate affection for him. Early on, say, at about two months old, as soon as I understood practically all of my father’s vocabulary, I understood why my mother didn’t love me. She didn’t really want to be a mother; she wanted to preserve her beauty and youth. I was an impediment to that.”

At this point, Pablo stopped, slightly moved. His relationship with his mother’s distant and indifferent personality had never been easy, but he had never wanted to admit to himself that she didn’t love him. He preferred to believe that she might have problems she didn’t want to share with others. But he pushed aside potentially unpleasant memories to concentrate on what he was reading. How could a baby perceive such things? He had known many geniuses and even a few savants in life, but never anyone who could remember the time they were in the womb.

“But my mother, with all her unmotherly coldness, did everything she could to compensate for her lack of affection for me with an excess of zeal for my father, and this in a way redeemed her in my eyes. Because my father was the kindest of men and deserved to be recognized for it. At one year old, I already communicated adequately well, certainly better than any other child I have ever known, because I understood everything I said and almost everything that was said to me. But I could not understand my parents’ arguments because they involved terms to which I could not attribute meaning. Even at this tender age, I began to feel the symptoms of my extraordinary curiosity that would haunt me throughout my life. I wanted to hear everything, touch everything, experience everything. But at the same time, I sensed that my parents, especially my father, needed a baby, and so I acted like a baby. Only, a baby who understood everything said to him. My abnormal development led my father, who was very perceptive, to ask himself if I would be gifted. At three years old, when I was already talking like a ten-year-old, he took me to a psychiatrist. I knew even then that gifted children can be separated from other children and even from their parents, and I didn’t want that. So, in psychiatric and educational tests, I acted like a normal child. The specialists who examined me concluded that I showed signs of being very intelligent, but only with time would a more accurate diagnosis be possible. That’s when I understood, from a very early age, that I was destined to be one thing and appear another. My father needed a normal son; that’s what he wanted, someone he could teach things to. So, at four years old, I could already read anything, but I pretended not to understand much so he would think he was teaching me. This made him happy, and it made me happy too. I confess that it was a hard struggle to pretend my intelligence was less developed than it was, but over time I got used to it. Because I wanted to study the world and the people around me, and this wouldn’t be possible if everyone thought I was a being from another world.”

Pablo placed the diary on the small table next to the armchair and looked around again, struck once again by the beauty and order of that library. He had never seen anything like it; everything was meticulously organized to reflect the personality and unique intelligence of its owner. On the enormous shelves, books of all sizes and thicknesses, but all carefully arranged in alphabetical order by author, and the vast majority of the names he saw, he had never heard of. Could his brother have possibly read that multitude of pages in his lifetime? On each shelf, a volume stood out. He imagined that these separate works must represent Juan’s favorites. Walking through the shelves, one book caught his eye: Jung’s Psychology and Alchemy. It was an old edition, beautifully bound. On the frontispiece, a dedication: “To Juan, my beloved friend, my partner in many hours of emotional debates,” António Avelar. Pablo remembered this Antonio as a colleague from Juan’s college days. He regretted never having had a deep conversation with his brother about anything.

"So I kind of forged two distinct personalities, one corresponding to a young person like any other. The other corresponding to who I really was. During my childhood and adolescence, I rarely suffered from the clash between these two facets of myself. Only a few times, at school, did I feel like a fish out of water when I had to take an interest in my classmates’ games when I really wanted to be studying. When I had to act like a normal kid, I often ended up embarrassing myself. But this only lasted until I was about fifteen. By then, I was ready to go to architecture school, as my father had encouraged me to do because of my ease with numbers and calculations. But I couldn’t get in yet because of my age. I already felt like I wanted to live on my own, so I wouldn’t have to always act like I didn’t want to. Then it happened that at this age, which corresponded for me to the end of puberty, I realized that I could not only read, and understand, any book I wanted in the school library. I could also “read” people. In other words, I could know in advance what people would say to me, how they would react to a given situation, and also what they expected of me in a given situation. This was crucial for me to finish school on par with the other students, even though I knew much more than any of my teachers. By “reading” what people expected of me, I knew how to act to avoid attracting attention. And so I was just another student in the class, and even when the time finally came to go to college, I still preferred to maintain the facade of a young man like any other.”

Pablo looked at his watch and realized he had already been inside that enormous house, unlike anything he had ever seen in his life, for two hours. Fortunately, for whatever reason, the electricity was still on. It was around four in the afternoon, and he glanced at his cell phone screen to see the message from his wife, asking what he thought of the house. He didn’t want to elaborate and simply replied that he was still checking the place out. He went back to reading.

"I entered the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism at the University of Buenos Aires in 1970, and they were some of the best years of my life. Of course, studying wasn’t a hindrance to me, and I could understand all the lessons just by reading the texts in the books once. But the experience was important because it was there that I met some professors who helped me understand my special condition without stigmatizing me. I had a kind of photographic memory that encompassed everything: texts, images, numbers, formulas, people, behaviors, trends. I just couldn’t literally predict the future. But other than that, I could know everything the professors would talk about in each class. One of these professors, the late and highly missed Dr. Guillermo Viñero, encouraged me to develop my intelligence through games like chess, which I had taught myself at age 14, and to write in detail about my experiences. At college, I also met a few lifelong friends, like António Avelar, who convinced me to buy this house in 1980, five years after my father’s death. After I graduated in 1975, I had no difficulty finding a job at the best architectural firm in Buenos Aires. By then, I was already living alone, but my beloved father’s death was still a shock. He was still so young, and I knew my promising career had made him very happy. I can’t describe what I felt upon learning of my father’s death. It was as if a part of me had been torn away, and I could no longer hold on to it. It wasn’t about emptiness, but the certainty that I would no longer have by my side that guy who, even though he was so different from me, was still the closest person I had in the world. I mourned for a month and even considered suicide, but I managed to overcome my anguish with the help of Roberta, a friend from college, who was also gifted and whom I would marry five years later.”

The mention of his father’s death reopened a wound that Pablo thought had healed 40 years ago. He still remembered how difficult it had been for him, then 15, to get over his father’s death. Enrico was a good father, albeit a strict one, but Pablo attributed this to his traditionalist upbringing. Losing him so young, and going to live with relatives he barely knew, instilled in him a certain sense of inadequacy that he would only overcome much later. Life in a distant place, the need to graduate and work, and also the encounter with his future wife all helped to heal the wound that was now reopened. Even so, he continued reading.

“I can’t say I felt the same way about my mother’s death, which happened shortly afterward. What I finally understood with her untimely death was that her emotional foundation in the world was her relationship to my father. She was never truly as close to her family as she was to her husband. I thank her for that, for being essentially good to him, although I don’t remember a single moment when she was good to me. When I realized I could “read” people, our situation worsened. Because I clearly perceived her indifference toward me, and for someone hypersensitive like me, that was horrifying. That’s why I also made a point of leaving home as soon as possible. Well, now in my own apartment, I was able to master my own cognitive abilities much better. Let’s just say, I could be myself in that small space. I took advantage of the opportunity to buy all the books I could and that would fit in the space. I read literally everything, from airport literature to astrophysics textbooks. I read magazines and comics. I watched all kinds of movies. I bought art books to “read” paintings and sculptures. The more I read, the faster my reading became, so much so that it took me a day to read about 500 pages at first, but after a while, if I had enough free time, I could read five or six books on different subjects in a single day. My mind never got tired. Of course, sometimes I had to clear my head and relax a bit to process the excess of information. I have a human body, after all. I started developing a hypnosis technique to force my overactive brain to “switch off.” It also helped me a lot with my friendships with António and Roberta. I had many interesting conversations with him, but he also had a great sense of humor and was a great time. Roberta, in turn, wanted to “cure” me of my book obsession. She wanted to take me on outings, to dinners, to socialize, whatever. Her great intelligence didn’t prevent her from being a very sociable person. Her thing was numbers; she could do any calculation in seconds. She established herself as an accountant early on and earned a lot of money because she did her work faster than any of her competitors. In fact, that’s how I learned to make money too. My work as an architect would have been enough to earn a good living, as I designed projects for the entire country. But with my sharp mind, designing a project was a breeze. I would look at a site plan, briefly study the local cartography, and immediately build in my mind an image of what the building the person wanted would look like. With this, and with the impeccable precision of my calculations and measurements, my fame grew very quickly. I began providing consulting services and creating projects for others. The best part was that work took up very little of my free time. I literally made a lot of money from a hobby.”